I often write pieces I never plan to submit for publication. These pieces are frequently passion projects that fall just outside of my aim as a researcher, but I still feel these short works deserve some public airing. They are often rough but shapely enough to relay their message. These short works conform to academic standards but are not peer reviewed. I hope you enjoy them! If you are a researcher, please make sure you cite me when quoting or using my ideas (this includes students; don’t get in trouble for plagiarizing; use MLA web citation format). Find full essay pages here: https://essaysbysean.wordpress.com/.

A Plea for Literature in College

By Sean Ferrier-Watson

Introduction

Crisis! That’s the word circulating among professors of English these days, particularly among those teaching and researching in literature. The numbers are devastating: students, course offerings, and professorships in English show dramatic losses over the last decade. This presumably perpetuated by the widespread belief that the study of writing serves little to no value, particularly in the world of modern business and finance. STEM and business are the name of the game. Higher education boards and college administrators facilitate the crisis by making sharp cuts to requirements and language department budgets across the board. Hiring has stalled within the profession. According to a report done by the Association of Departments of English (ADE) and published by the Modern Language Association (MLA) in 2008, “Over [a] ten-year period, the proportion of the faculty made up of tenure-line faculty members fell 10.1 percentage points, or 23.9%, from 42.3% to 32.2%” (3). This is roughly the loss of about one percent per year. In his viral article “Academe’s Extinction Event: Failure, Whiskey, and Professional Collapse at the MLA” (2019), Andrew Kay shows the demise of language studies in haunting terms,

“All around them [professors], the humanities burned. The number of jobs in English advertised on the annual MLA job list has declined by 55 percent since 2008; adjuncts now account for all but a quarter of college instructors generally. Whole departments are being extirpated by administrators with utilitarian visions; from 2013 to 2016, colleges cut 651 foreign-language programs. Meanwhile the number of English majors at most universities continues to swoon”

It couldn’t sound any drearier, yet many applaud the decline (even within the academic landscape). While many STEM and business professors advocate for well-rounded education, most are happy to see their budgets and student populations swell because of this decline in language studies. Within some conservative political circles, the English professor is the face of liberalism and the antithesis of all they oppose (something far from true in reality).

If these claims of worthlessness and antagonism hold weight, then the evisceration of language studies, particularly the study of literature, should be cause for little concern, but the numbers on the advantages to studying literature and language tell a different story. The attack on literature and language studies has come at a great cost. According to the MLA in their piece “Language and Literacy in the U.S. Going in the Wrong Direction,” verbal skills and literacy in general are in decline, especially over the last few decades, roughly around the same time this assault on literature and language studies accelerated. Their research shows an 8% drop in SAT verbal skills from 1968 to 2014. 12th grade students “at or above proficiency” fell 40% to 37%. Between 1992 and 2008, reading for pleasure among U.S. citizens dropped by 11% and families “reading to children declined by 8%.” This while some states described language and literature curricula as, “an expendable…luxury that taxpayers should not be expected to pay for” (see “A Rising Call to Promote STEM Education and Cut Liberal Arts Funding” in the New York Times).

This decline in literacy is but one of the critical losses inflicted by the decimation of literature studies throughout higher education. Literature has long been a staple of the humanities and one of the grand pillars of education, covering the entire array of human experience—psychology, politics, science, history, philosophy, and art all fall within literature’s vast domain. Its history spans thousands of years. Aristotle, roughly two- thousand years ago, analyzed literary theory and technique in his great Poetics. His theory on the definitions of tragedy and comedy still holds sway today. Literature is a dominating force in our world and evidence of this emerges everywhere. From Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale’s (1985) influence on the political arena to The Hunger Game’s (2008) empowering heroine and role-model Katniss, literature dominates our cultural conversation. Story is an essential part of the human condition: it is the way we perceive and understand the world. We interpret our lives, faiths, and businesses through narrative, through layers of story simple and complex. It is the foundation of our existence, but lately it is being diminished in our college education. Students walk out the door of our universities and colleges with little knowledge about the stories influencing their world and with even less knowledge about ways of interpreting them. Literature is the cornerstone of the humanities and essential to a well-rounded education.

The Economy of Literature

For those more economically minded, literature is also a billion-dollar industry. If you find that claim doubtful, consider the industries that thrive from the wellspring of literary achievement. J. K. Rowling’s book sales alone are quite an economic accomplishment. She has sold more than five-hundred million books to date in her Harry Potter series. Some of the most successful movie and television franchises hail from literary works: The Lord of Rings (2001-2003), Game of Thrones (2011-2019), The Hunger Games (2012-2015), It (2017-present), Twilight (2008-2012), Jurassic Park (1993-present), James Bond (1963-present), and even the Avengers (2012-present) are adaptations of literary works, print narratives. Classic literature also finds its way into popular adaptation. God of War (2015-2018) and Dante’s Inferno (2010) are successful game franchises based on adaptations of the works of Homer and Dante. These literary franchises support hundreds of industries and millions of jobs, employing graphic designers, advertisers, directors, coders, producers, and numerous other occupations—not to mention the abundance of merchandise produced because of these franchises. If you believe all these innovators were English majors, you would be dead wrong, but many of them did take literature courses in high school and college. They may not have seen the benefits at the time, but they likely see the rewards of these classes in their current success. Literature inspires and innovates industry world wide. Why would we want to deprive our college graduates of this opportunity? It would be a mistake to remove access to such innovations.

According to Stephen A. Raynie (2013), industry leaders value the study of literature and desire employees with a background in the subject. He argues that English majors obtain critical thinking and soft skills employers want through their study of language and literature. He indicates CEOs such as Bracken Darrell and Bruna Martinnuzzi have attested to the value of seeing employees with a background in English, particularly in literary study (82-3). Sheryl Fontaine and Stephen J. Mexal (2014) see similar value to the benefits of studying literature. In their article “Closing Deals with Hamlet’s Help: Assessing the Instrumental Value of an English Degree,” they survey their English alumni and find that their alumni see professional benefits to their literary studies:

“There are a significant number of English department alumni who are not employed to read, teach, or think about, say, Shakespeare, who nonetheless have derived instrumental, professional utility from reading and thinking about Shakespeare as college students. To put it a different way: Someone’s closing deals with Hamlet’s help” (369-7).

They also found that 84% of their respondents saw positive benefits to their written communication and 83.6% claimed their analytical reading skills improved because of their studies (367-8). This is beneficial to all our college graduates. We should strive to strengthen our students’ abilities to think and write critically, regardless of what practical alignment benefits are at stake. Our students and their education are at the heart of every college mission statement and their future success benefits all of humanity.

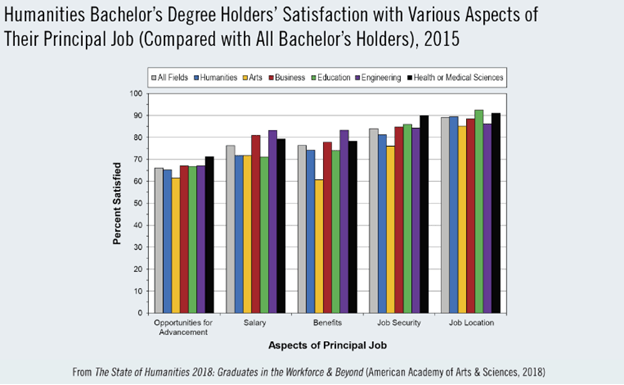

Despite the popular stereotypes, English and humanities majors do quite well on the job market, often rivaling their counterparts in business and science. “The data are clear that English graduates find jobs and earn competitive wages,” argues Raynie. “Like other students in the liberal arts and sciences, English majors cultivate a cognitive strength in college that serves them well as they later find work in a competitive market” (82). Raynie’s assertion is supported by other studies into the subject as well. According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, humanities majors are on par with most business and science majors, demonstrated by the graph below:

The study goes on to concluded Humanities majors are happier in their pursuits than most other majors with high levels of satisfaction in salary, benefits, job security, and job location:

These numbers help to make an important point: humanities and English focused students are doing just fine when they leave colleges throughout the country. Our degrees and courses are doing their jobs. We should take stock in these numbers and keep up our productivity by deepening our commitment to literature in college. We are not letting our students down by giving them literature along their degree path, and we should resist efforts to minimize the teaching of literature in college. If anything, we need to work harder to explain to our students the benefits of literature to their future happiness and success.

Conclusion

Literature is a valuable subject. As Raynie contends, “English needs to promote itself for what it is: a discipline of intellectual richness that enables people to lead fulfilling, prosperous lives in a variety of fields” (77). I tend to agree with Raynie’s sentiment. As I have shown in this brief essay, literature courses serve both a practical and educational purpose for college students. We should push students to explore literature with earnestness as they seek degrees that will help define their futures. Literature is not a “soft” or “outdate” subject: it is vital to education and paramount to the success of humanity. We live in a storied world and we need to train our future generations how to interpret and transform these stories. Our survival may one day depend on it.

Works Cited

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. “State of the Humanities 2018.” Amacad, 10 Dec. 2018, https://www.amacad.org/content/publications/pubContent.aspx?d=43083

Cahill, Maria J., and Scott Ortolano. “Introduction: Sustaining English Programs in the Twenty-First Century.” South Atlantic Review, vol. 78, no. 1/2, 2013, pp. 4–9. JSTOR, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43739029.

“Education in the Balance: A Report on the Academic Workforce in English (Report of the ADE Ad Hoc Committee on Staffing.” MLA, 10 Dec. 2008, https://www.mla.org/content/ download/3255/81374/workforce_rpt03.pdf.

Fontaine, Sheryl I., and Stephen J. Mexal. “Closing Deals with Hamlet’s Help: Assessing the Instrumental Value of an English Degree.” College English, vol. 76, no. 4, 2014, pp. 357–378. JSTOR, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24238297.

Kay, Andrew. “Academe’s Extinction Event” Failure, Whiskey, and Professional Collapse at the MLA.” Chronical, 10 May 2019, https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/20190510-academes-extinction-event.

King, Tabitha, and Marsha DeFilippo. “The Author.” StephenKing, 10 Dec. 2018, https://www.stephenking.com/the_author.html.

“Language and Literacy in the U.S. Going in the Wrong Direction.” MLA, https://www.mla.org/content/download/52219/1812312/Infographic-Language-and-Literacy-3.pdf.

Raynie, Stephen A. “Selling the English BA Program.” South Atlantic Review, vol. 78, no. 1/2, 2013, pp. 76–94. JSTOR, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43739033.

“Writing.” Jkrowling, 10 Dec. 2018, https://www.jkrowling.com/writing/.

Updated: 6/18/2019

Buying Their Words: Consumer Students, Corporate Colleges, and the Paper Mill

by Sean Ferrier-Watson

With the publication of “The Shadow Scholar” in The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2010, the issue of plagiarism, particularly the issue of the “paper mill” industry, has returned to the academic limelight. “The Shadow Scholar” has seemly touched a nerve with academics. The Chronicle reported that “[t]he article…received more than 640 comments, the most on any article published by The Chronicle” (“Something is Rotten in Academe” B16). This unprecedented outpouring of interest reflects the levels of shock and concern reverberating throughout academia in response to the “paper mill” industry. While paper mills are certainly nothing new to the academic arena, the Shadow Scholar, Mr. Dante, has revealed the persistent growth of a troubling trend: the purchasing of original manuscripts by students through highly organized and professional businesses. The existence and growth of this industry has caused many academics from multiple disciplines to search for the cause and subsequent solution to this issue in three ways: introspective reexamination of pedagogy, where blame and resolution seem to rest on the professor; external reexamination of student motives, where blame and resolution rest on studying and reforming the student; and administrative prevention, where blame and resolution rest firmly on the poor screening abilities of professors, administrators, and prevention software like Turnitin.com. While all three of these modes play an intricate part in curtailing plagiarism and the paper mill industry, the second focus concerning a deeper examination of the student’s motives for using purchased manuscripts seems far more promising a starting point for identifying the cause of the epidemic, if indeed there is one.

The reason students decide to plagiarize is a contentious issue among scholars, with some advocating that students commit the act out of confusion or desperation while others contend that students consciously and deviously conspire to plagiarize. Rebecca Moore Howard, a prominent scholar on the plagiarism issue, argues that plagiarism is “inherently indefinable” because in practice it is tied to a number of social, historical, and biological metaphors that render a clear definition impossible (473). “Embedded in the discursive construction of plagiarism,” Howard argues, “are metaphors of gender, weakness, collaboration, disease, adultery, rape, and property that communicate a fear of violating sexual as well as textual boundaries” (474). Susan D. Blum, in her book My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture, finds similar confusion over the term plagiarism in her study and contends that contemporary students struggle with the term because they view text in a different way than past generations, claiming “[t]oday’s students stand at the crossroads of a new way of conceiving texts and the people who create them and who quote them” (6). Unlike Blum and Howard, Mathew C. Woessner argues “that faculty members have an ethical responsibility to severely discipline students who overtly engage in academic plagiarism” (313). He asserts that faculty members will in fact encourage plagiarism by showing leniency (313).

The above scholars show the maelstrom of dissension over the issue of plagiarism and its many implications, and the very existence of such a maelstrom insinuates the complexity of the plagiarism issue. As such, it is necessary to investigate the issue of plagiarism from many perspectives and to investigate what even appear to be clear-cut cases of plagiarism. Scholarly attention on the issue of purchased papers or paper mill plagiarism is seldom investigated as unintentional by most plagiarism scholars. The argument, as Laura Hennessey DeSena phrases it, is as follows: “If an entire paper has been purchased or taken from an online site (or from anywhere else for that matter) then this is clearly a blatant case of plagiarism and must be dealt with according to school policy” (emphasis added) (47). The assumption being that the act of buying a paper constitutes knowledge of the offense, but this, of course, assumes the student is conscious of the ethical dilemma such an act represents in academia. If contemporary students are carrying varied social and ethical perspectives on authorship as Blum and Howard suggest above, then it might also be possible that students perceive authorship and ownership in different ways than previous generations, which might account for such seemingly unethical acts as obvious plagiarism by students.

Kelly Ritter, in “The Economics of Authorship: Online Paper Mills, Student Writers, and First-Year Composition,” contends that contemporary students operate under a consumer mindset rather than the idealized academic mindset of authorship, indicating that contemporary first-year writing students fail to see themselves as authors and confuse authorship with ownership in terms of paper writing and purchasing (602-3). Ritter’s assertion is apt to the current paper mill dilemma in academia, but her argument fails to capture one very important thread in this elaborate tapestry of consumerism, authorship, and plagiarism. Her analysis fails to acknowledge the university’s involvement in facilitating the growth of a consumer mindset within the modern academy, a mindset which contributes directly to the growth and success of the paper mill industry. I speak, of course, of the growing corporatization of academia and its role in reinforcing the consumer academic-mindset in contemporary students. This growing trend in academia, coupled with students’ consumer views entering college, compounds students’ use of paper mills and confusion over authorship.

The corporatization of universities is hardly a new subject to most academics, but its implications on student development and education have scarcely been discussed by contemporary scholars. In “Student Ratings in a Consumerist Academy: Leveraging Pedagogical Control and Authority,” Jordan J. Titus discusses the implications and ramifications of corporatizing universities. His research indicates that academia has become more conducive to the “student-as-consumer” model than to the “student-as-learner” model (397-8). Titus clarifies this argument in the following observation:

“A basic assumption of marketing in higher education is that increased competition will have a positive impact because it will force providers to respond to student pressure or risk losing potential customers. Institutionalization of the student-consumer metaphor has been accompanied by a transformation of what is considered education, from a process (e.g., of becoming more learned) to a product (such as a degree). An implication is that universities will shape the services they offer to please students’ tastes, and faculty will responsively teach to students’ preferences” (398-9).

Titus’ observation about the corporatization of academia has considerable implications on the student’s role in academia. If the academy is moving toward a more corporate, consumer focused system, then it is not farfetched then when students imagine themselves as customers of the university, paying good money to obtain their desired product—a college degree. And as any savvy consumer, they are also trying to get the most “bang for their buck” (Ritter 608). If paper mills expedite the acquisition of their degrees, these consumer minded students might see using such industries as a prudent means of completing taxing and expensive coursework.

While universities certainly disdain such notions of student consumerism in policy, they certainly appeal to this mindset in all other areas of a students’ academic life: marketing and consumerism are evident in the university bookstores, food courts, course packages, and sporting facilities; they are apparent in ads and degree criteria, where students are promised certain courses and degrees for specific prices; and they are even noticeable in the way administrators track course evaluations. Ritter argues scholars have missed such obvious connections between consumerism and students because scholars are so closely connected with consumerism themselves:

“I suspect that we [scholars] have thus far dismissed online paper-mill patronage as a site of study because this type of academic dishonesty goes to the core of our popular, capitalist culture, itself predicated on the exchange of specialized, even personalized, goods and services, of which papers-for-sale are only one possibility” (606).

While Ritter does not go as far as to extend this argument to academia in general, she does establish the grounds in which to make the connection between academia and consumer culture. Certainly the recent increase in administrative demand for course or student evaluations and the pressure on faculty to retain students are evidence of this growing trend throughout modern academia.

According to Jordan J. Titus, student evaluations are primarily employed as a means of making sure faculty are satisfying their student consumer needs. He pays specific attention to the flaws of student evaluations of teaching (SETs) in order to demonstrate how such evaluations neutralize the faculty as teachers:

“By looking beneath the rating numbers to the meanings for the raters of the categories on which they evaluate faculty, what is revealed is that students’ expectations are based on a conception of teaching and learning qualitatively distinct from the pedagogical views of faculty. Student expectations are found to be framed by a transmission model of education that is both a central aspect of the consumer mentality and the only form of teaching that the rating instrument represents. The argument advanced here is that in serving a consumerist academy, the use of SETs functions to reframe the relationship between instructors and students through promoting a passive model of learning and deterring critical inquiry” (399).

Titus’ concern is that the instructor’s role as teacher is being neutralized by the university’s desire to please its students/customers. His argument that students see learning as a passive transmission of knowledge rather than an active engagement of knowledge demonstrates contemporary students’ disconnect when it comes to authoring papers. If students believe that knowledge is passive, then they will assume that writing is also a passive action, which only requires them to reproduce the expected knowledge, not examine, question, approve, or denounce it. From this passive knowledge transmission perspective, purchasing writing from a paper mill seems like a perfectly legitimate option: it enhances the passive transmission of knowledge while simultaneously satisfying the student consumer’s needs.

Ed Dante also notes this kind of student in his article to The Chronicle of Higher Education. He identifies this student as the lazy rich student and compares this student to what he calls the deficient student. “While the deficient student will generally not know how to ask for what he wants until he doesn’t get it,” claims Dante, “the lazy rich student will know exactly what he wants. He is poised for a life of paying others and telling them what to do. Indeed, he is acquiring all the skills he needs to stay on top” (B8). While Dante makes many assumptions about this kind of student, he is at least seemingly correct in assuming the student’s passive role in knowledge transmission. The consumer student (even the deficient and ESL student) values the ability to select and ask for the appropriate discourse, but fails to see the advantage of the discourse beyond this, largely because the consumer or business person only needs to appropriate the knowledge to the extent of acquiring the correct product.

The consumer students’ valuing of the passive transmission of knowledge is also linked to the confusion many of these students have in regards to ownership versus authorship. Ritter contends that contemporary students routinely conflate authorship with ownership, arguing “…a student who buys a paper with the author’s permission has stolen nothing” (615). Since these students do not see the act of theft or understand what academics mean by authorship, they assume the authorship of the paper must have been transferred during the transaction (615-6). To add to Ritter’s argument, it is also likely the student assumes the act of purchasing a paper through a genuine transaction (i.e. credit card or check) legitimizes the transference of authorship/ownership. Many students might assume that illegal or suspicious transactions are conducted in cash and behind closed doors, and the fact that online paper mills are able to use credit cards and operate openly on the internet might suggest to them that these business are legitimate.

It is also important to note that these students’ literacy practices might also be grounded in consumer culture. According to Kathryn Valentine, a composition and literacy scholar, “[p]lagiarism becomes plagiarism as part of a practice that involves participants’ values, attitudes, and feelings as well as their social relationships to each other and to the institutions in which they work” (89-90). With popular media, family, friends, and the university reinforcing notions of consumerism, it is not surprising then that many students might easily confuse such consumer notions with scholarly values. Valentine argues the ethical dilemma around plagiarisms is further compounded by the discourse academics use to discuss plagiarism; the very act of categorizing and labeling plagiarism and students who commit plagiarism with language signifying an ethical failing complicates the student’s identity within the institution and potentially compromises the validity of their literacy practices (90). Such a notion challenges the idea that academics even have the right to regulate or judge plagiarism in the first place. If plagiarism arises from legitimate social practices, as Valentine seems to indicate, then it becomes harder for academics to simply polarize the issue and call it unethical.

Margaret Price also seems to note the dubious practice of regulating plagiarism within academia. In her article “Beyond ‘Gotcha!’: Situating Plagiarism in Policy and Pedagogy,’ she questions the legitimacy of plagiarism policies and their pedagogical message:

“For the past several years, I’ve become increasingly dissatisfied with available explanations of plagiarism, particularly the ones on written policies that I’ve duplicated and distributed. The tone of such policies seems focused on a pedagogy whose spirit we might characterize as “Gotcha!” Plagiarism is not only a phenomenon that can be mastered by students new to academic writing, such policies announce, it must be mastered. Being caught plagiarizing results, as the policy usually stipulates, in severe penalties” (89).

Price indicates that plagiarism policies usually only serve one pedagogical purpose in the classroom: to provide the instructor with the leverage to capture students plagiarizing. Price, of course, is correct on this point. Beyond the administrative purpose of catching plagiarism, most plagiarism policies are fairly useless. They only act as a crutch for teachers to enforce the rules regulating cheating at a particular institution, and students will either master these rules and avoid or manipulate plagiarism or fail to master these rules and plagiarize accidentally. Within the current construction of most plagiarism policies, the space to teach or reflect on plagiarism is rarely available, offering little ground for a true dialogue to exist between instructors and students.

For the consumer-student-plagiarist, plagiarism policies are an ironic subversion of the practices and mores they encounter within their culture and the university’s exterior culture. It is not surprising then that they misread such policies or ignore them altogether. Many plagiarism policies are presumptuous about language consumer minded students might find confusing or ambiguous. As already stated, author and own can carry a very different meaning for students than for academics. Price is quick to make this distinction as well, arguing that the “[k]ey to avoiding plagiarism, I am told again and again, is identifying the parts of an essay that are a writer’s own words, her own ideas. Figuring out what we mean by the concept of ‘own’ is the rub” (94). For most first-year students, the word own carries deep seated consumerist connotations, which are buried in notions of financial transaction, marketing, and use privileges which undermine the practices enforced by most university plagiarism policies. These connotations provide incredible hurtles to instructors and administrators attempting to reverse such notions.

How then can faculty combat this consumer-student mindset in their classrooms? With universities and students moving further into consumer culture, it seems difficult for faculty to resist a potentially dangerous trend growing all around them. However, Jordon J. Titus contends faculty must resist this trend and that the classroom is ground zero for such an assault: “Academic and professional ethics require that professors take responsibility for defining what will count as good teaching––and its measure. Accountability for students’ learning cannot be replaced by an accountability for satisfied consumers” (414). While Titus is speaking specifically of student evaluations, his insinuation that consumerism must be resisted by faculty in the classroom at all costs is evident. Teachers do have an ethical responsibility to teach their students to the best of their abilities, which means finding a feasible approach to dealing with paper mill or consumer plagiarism is a top priority.

Since much of the cause of consumer plagiarism is linked to concept confusion and anxiety over coursework, it makes sense for instructors to begin with pedagogical approaches that will alleviate these concerns. For instance, instructors should take time to discuss notions of authorship within their discipline as frequently as possible, taking time to explain the policy and what is meant by the language in the policy. Having students discuss notions of ownership in relation to authorship is a good place to open a discourse about plagiarism. The more students discuss the issue the more likely they are to understand it. It might also be prudent for instructors to explain the goals of their discipline. Many instructors assume the mission and purpose of their profession is self-evident, believing that students see the value in their discipline just as they do. However, students do not always see intrinsic values within academic disciplines outside of their interests. They may not readily understand the value of a novel or the purpose in analyzing it, nor might they readily see the value in studying evolution, culture, or math without explanation. Faculty should justify their discipline’s existence to their students. If students learn the discipline’s value, they will be more likely to engage the discipline’s practices and work. Finally, faculty should always try to convey a sense of accessibility in terms of grading and course content. They should let their students know they are willing to work with them and that hard workers never need to turn to plagiarism to finish difficult assignments.

While the suggestions listed above are simple in nature, they might do a lot to curve some of the consumer plagiarism issues in contemporary classrooms. Faculty should always be mindful of student’s concerns and the ideologies their universities are portraying to present and future students. If faculty continue to reach out to students and address their concerns, students will likely make an attempt to learn these practices and avoid plagiarism. Ed Dante might contend in his article that students are too devious or deficient to engage these practices, but his experience with these students is limited simply to the other side of a computer terminal and the assignment the student is struggling with. Faculty, on the other hand, have the ability to engage the students weekly in open forum. As long as faculty take advantage of this open forum and use it to explain the practices of their discipline, plagiarism problems, including the paper mill industry, can be remedied, and instructors can demonstrate to their students ideas unregulated by a consumerist society.

Works Cited

Blum, Susan D. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press, 2010. Print.

Dante, Ed. “The Shadow Scholar.” Chronicle of Higher Education 57.13 (2010): B6-B9. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 1 Aug. 2011

DeSena, Laura Hennessey. Preventing Plagiarism: Tips and Techniques. Urbana (IL): National Council of Teachers of English, 2007. Print.

Howard, Rebecca Moore. “Sexuality, Textuality: The Cultural Work of Plagiarism.” College English 62.4 (March 2000): 473-91. Print.

Price, Margaret. “Beyond ‘Gotcha!’: Situating Plagiarism in Policy and Pedagogy.” College Composition and Communication 54.1 (September 2002): 88-115. Print.

Ritter, Kelly. “The Economics of Authorship: Online Paper Mills, Student Writers, and First-Year Composition.” College Composition and Communication 56.4 (June 2005): 601-31. Print.

“Something Is Rotten in Academe.” Chronicle of Higher Education 57.19 (2011): B16-B17. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 1 Aug. 2011.

Titus, Jordan J. “Student Ratings in a Consumerist Academy: Leveraging Pedagogical Control and Authority.” Sociological Perspectives 51.2 (Summer 2008): 397-422. Print.

Valentine, Kathryn. “Plagiarism as Literacy Practice: Recognizing and Rethinking Ethical Binaries.” College Composition and Communication 58.1 (September 2006): 89-109. Print.

Woessner, Matthew C. “Beating the House: How Inadequate Penalties for Cheating Make Plagiarism an Excellent Gamble.” PS: Political Science and Politics 37.2 (April 2004): 313-20. Print.

[The above essays was adapted from a presentation I gave at the 10th Annual A&M Pathways Symposium in 2012.]

6/17/2019